śrī śrī guru gaurāṅga jayataḥ!

Year-4, Issue 11

Posted: 15 December, 2011

Dedicated to

nitya-līlā praviṣṭa oṁ viṣṇupāda

Śrī Śrīmad Bhakti Prajñāna Keśava Gosvāmī Mahārāja

Inspired by and under the guidance of

nitya-līlā praviṣṭa oṁ viṣṇupāda

Śrī Śrīmad Bhaktivedānta Nārāyaṇa Gosvāmī Mahārāja

When the Transcendental Sound

Makes His Appearance

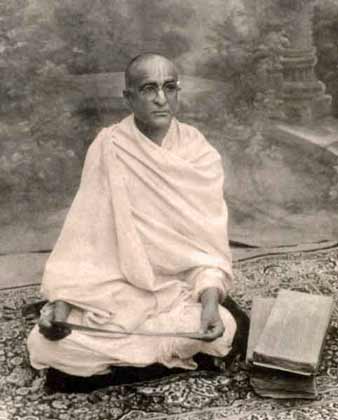

by Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura Prabhupāda

When the Transcendental Sound makes His appearance, we must not adopt a challenging mood and suppose that it also has a material face. The two types of sound – the transcendent and the mundane – are quite distinct from one another. Mundane sound is meant for entities that have phenomenal figure, odour, taste, and so on. Heat, for example, can be perceived by the sound it circumstantially produces. Yet although such sound expresses a feature of what seems to be, it need not actually coincide with the truly abiding substratum. So there is a distinct difference between the two types sound.

All Transcendental Sounds move to reveal one object: the Absolute. Wherever any sound deviates from the Absolute, that which it indicates is liable to vanish. Absolute sound has His peculiar phase and should be welcomed at all costs. We are vitally interested in that thing. In the very definition of Transcendental Sound it is unveiled to us that the Transcendental Sound is identical with its object, its qualities, and its activities; that it is entirely distinct from mundane sound; and that it is equipped with all the appropriate potencies for regulating all of our senses.

Mundane sound is invigorating to the senses and enables us to come in contact with the world. When our attempt is for the Absolute, we run no risk. When we want mundane sound to come to us, we ignore the Absolute and thus we do not receive the Transcendental Sound. The Transcendental Sound relates strictly to the Absolute, so when we determine our true self, we shall comprehend the Absolute. Any distortion in our conception will prevent us from approaching the Absolute.

First of all, we should examine our self. If we think we are the mind and the external body, the Transcendental Sound will have no effect on us, for that is the domain of mundane sound. The Transcendental Sound Himself will tell us that the external body is but a garment of the inner, astral body, and those bodies are the two coverings of the soul who, in his dormant condition, incorporates them, despite their inability to unveil his own real nature. The external body is perishable; the internal body is transformable. Our mind in the morning is different from our mind at noon and so on. It is changed by the passing of time.

We cannot rely upon the mind or our mental speculation. All of us are busy making our mind control everything related to us. But this behaviour does not acknowledge the conception of the Absolute. Mental conceptions are always mutable. The property must not be confounded with the proprietor, and our external body is but our property. It is perishable and there is no certainty of its retention.

In ancient Egypt, the body was preserved because it was thought to be a necessary process for the reawakening of the soul. The materialists see the externality of things. They observe that the combination of material particles seems to produce animation. And so, the materialistic sciences scrutinize the external.

Adapted from The Gaudiya, Volume 28, Number 3–4

by the Rays of The Harmonist team